Wildfires are a natural occurrence in Oregon’s forests, especially in the state’s “dry forests,” where periodic burns actually contribute to overall forest health. Many plants and trees have adapted to wildfires, and some species can’t survive without them. For example, a lodgepole pine needs heat from wildfires for its cones to open and release seeds. In central and eastern Oregon, periodic low-intensity wildfires burn away smaller trees and brush. This fosters the regrowth of new trees and plants.

But fire suppression practices over the past 100 years have created overly dense forests, fueling bigger and more destructive wildfires. Climate change may be another reason Oregon’s wildfire seasons are getting longer.

People start a large number of wildfires in Oregon. Major culprits include backyard burn piles and unattended campfires, according to the nonprofit fire prevention organization Keep Oregon Green.

Whether sparked by lightning or human-caused, wildfires can harm fish and wildlife habitat and damage nearby homes or other structures. They’re often costly to extinguish and can negatively affect air and water quality.

Visit FireAmongUs.org. Being safe with fire is one of the most important ways to reduce the threat of human-caused fire. This illustrated microsite joins the characters of the forest as they walk you through the basics of fire science, and how to make smart choices with fire in and around a forest.

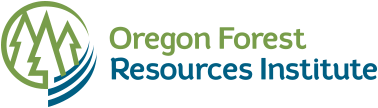

Historic fire behavior

Fire has always been part of forest ecosystems in Oregon, and has shaped forests in various regions of the state differently:

Dry forests

In the dry ponderosa pine forests of central and eastern Oregon, fire historically burned through any given area every two to 25 years. But the fires generally were not intense. Understory plants were burned off, but large trees usually survived.

Wet forests

In the wet Douglas-fir forests on the west side of the Cascades and in the Coast Range, fire in any given stand is much less frequent, once every 200 to several hundred years. The historic record shows numerous instances of large, intense fires that killed most of the forest.

Southwestern Oregon forests

Interior southwestern Oregon forests experience some of the dryness of east-side forests, but with productivity more like west-side forests. They have intermediate fire behavior, and historically burned with mixed severity every 25 to 50 years.

Suppression is expensive

To protect human lives and structures, it’s often necessary to suppress wildfires. In fact, over the past decade Oregon has spent more than $226 million fighting forest fires on state-protected lands.

Fire suppression, while beneficial in the short term, can have long-term negative effects. The exclusion of natural wildfire can, over decades, result in dense, overstocked forests with an overabundance of understory that would normally be removed by natural fires. These forests will inevitably experience fire, but with potentially much more devastating results.

With so much fuel on the ground and so little space between trees in these unnaturally dense forests, fires are more destructive than the frequent low-intensity wildfires that once naturally thinned out smaller trees and underbrush. When dry brush and shrubs aren’t cleared away, they can become “ladder fuels” that make it possible for fire to reach the top of the forest canopy, which can kill entire trees.

Intense fires can also harm water quality and alter soil characteristics. This increases the chances of erosion, and can hinder post-wildfire reforestation efforts and the forest’s natural ability to regenerate.

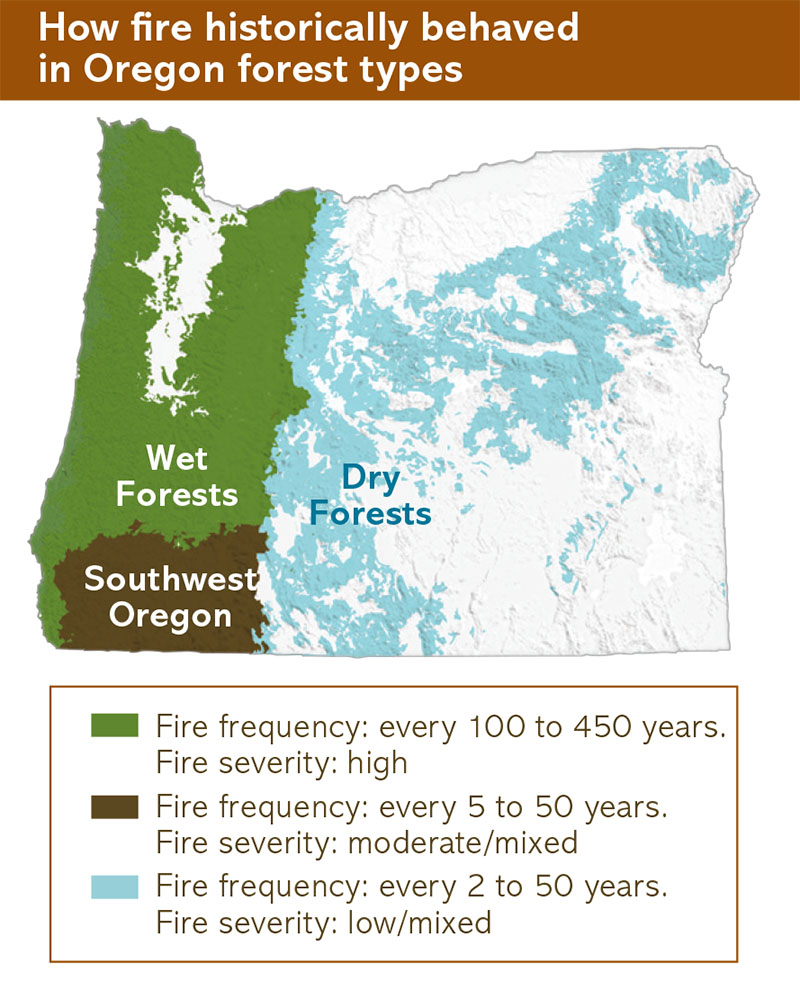

Forest restoration

The state and federal government, as well as local stakeholders, are working together with logging contractors to accelerate the restoration of central and eastern Oregon federal forests back to the conditions they were in before wildfire suppression allowed them to become unnaturally dense and prone to destructive fires.

These restoration projects involve active forest management, including thinning trees, mowing dry brush and prescribed burning, to improve forest health and fire resiliency. Restoring more open forest conditions through thinning makes it harder for wildfires to become large, catastrophic fires. Thinning also decreases the competition among the remaining trees, allowing them to grow larger, healthier and more fire-resistant. Prescribed burns mimic the natural role fires play in forests by clearing away brush and having a rejuvenating effect on plants and trees.

Forest Threats: Forest Fire

Fire can be a particularly destructive threat to Oregon’s forests, but active forest management can help lessen the impacts.

Forest collaborative groups

In central and eastern Oregon, forest collaborative groups are bringing together a diverse group of stakeholders, including representatives from the conservation community and the timber industry, to find consensus on improving the fire resiliency of public forests.

Group members are developing “zones of agreement” on ways to make federal forests less prone to larger, more destructive wildfires while achieving economic and environmental benefits. The goal is to give the U.S. Forest Service candid feedback on restoration projects and avoid gridlock caused by lawsuits that stop timber harvests.

Federal forest restoration projects support jobs with local logging companies and lumber mills. Revenue from harvested timber also helps pay for related efforts such as wildlife habitat enhancement and stream restoration.

Oregon has more than two dozen collaborative groups, involving hundreds of Oregonians working together to find common ground on forest restoration and other important federal forest management issues across the state.